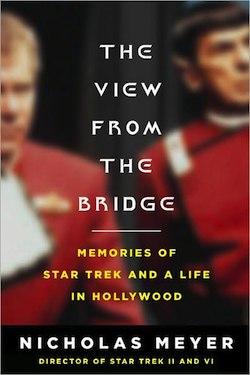

For our Star Trek Movie Marathon, please enjoy this excerpt from The View From the Bridge by Nicholas Meyer, available now from Penguin Books. In this memoir, Meyer details his experiences working on the Star Trek films. Read more to discover how twelve days and a brilliant script overhaul saved The Wrath of Khan.

***

Star Trek vaguely reminded me of something, something for which I had great affection. It took me quite a while before I realized what it was. I remember waking with a start one night and saying it aloud:

“Hornblower!”

When I was a teenager I had devoured a series of novels by the English author C. S. Forrester (author of The African Queen and Sink the Bismarck!, among other favorites), concerning an English sea captain, Horatio Hornblower, and his adventures during the Napoleonic wars. “Horatio” as a first name was the giveaway; Hornblower was clearly based on Lord Nelson, though I’ve recently learned his surname derived from that of Hollywood producer Arthur Hornblow, Jr., a friend of Forrester’s. There was also a beloved movie version, Raoul Walsh’s The Adventures of Captain Horatio Hornblower, starring Gregory Peck and Virginia Mayo. (In the picaresque film, Hornblower faces off with the malignant and memorable El Supremo. Watching the film later as an adult, I understood that El Supremo, the frothing megalomaniac, was a racist caricature, the more so as he was played by a Caucasian in “swarthy” face, the UK-born Alec Mango. Khan Noonian Singh, by contrast, was a genuine (if oddly named) superman, embodied by a superb actor who happened to be Hispanic. Khan was a cunning, remorseless, but witty adversary—his true triumph being that audiences adored his Lear-inflected villainy as much as they responded to Kirk’s enraged heroism.)

Hornblower has had many descendants besides Kirk. Another Englishman, Alexander Kent, wrote a series of similar seafaring tales, and Patrick O’Brien’s Aubrey-Maturin novels are an upmarket version of same—Jane Austen on the high seas—one of which became the splendid film Master and Commander. Still another Englishman, Bernard Cornwell, produced a landlocked version of Hornblower in the character of Sharpe, a swaggering, blue-collar hero of the Peninsular War.

I asked myself, What was Star Trek but Hornblower in outer space? The doughty captain with a girl in every port and adventure lurking in each latitude? Like Hornblower, whose gruff exterior conceals a heart of humanity, Kirk is the sort of captain any crew would like to serve under. Like his oceanic counterpart, he is intelligent but real, compassionate but fearless, attractive to women but not precisely a rake. For prepubescent—(and for that matter post-pubescent)—boys such as myself, Hornblower-Kirk conceals the sort of Lone Ranger–D’Artagnan–Scarlet Pimpernel hero we liked to fantasize about being, the steady guy with a dashing secret identity. Hornblower-Kirk’s secret identity was folded into his own persona, but the notion still holds. (A case might also be made, I suppose, that James Bond is yet another offspring of Forrester’s hero.)

Once I was possessed of this epiphany, a great many things fell readily into place. I suddenly knew what Star Trek wanted to be and how I could relate to it. The look of the film and the natures of the characters—even their language—suddenly became clear. And doable. I would write a Hornblower script, simply relocating in outer space.

That left the question of the script itself, and therein came my second brainstorm. I invited Bennett and his producing partner, Robert Sallin, to sit down with me at my place, where I laid it out for them.

Sallin, who owned his own commercial-producing company, was a dapper, diminutive ex-military man with a clipped, Ronald Colman mustache and agreeable manners. He and Bennett had been close friends at UCLA, and the Star Trek project was seen by Bennett as a chance for them to work together. (By the time the film was finished, they would no longer be speaking).

They listened as I explained my Hornblower thesis and notion of reconfiguring the look and language of the original series. I didn’t like the idea of everyone running around wearing what looked to me like Doctor Dentons and couldn’t make out why people said “negative” when they meant “no,” or why no one ever read a book or lit a cigarette.

In this, I was ignorant of Star Trek’s history and more especially of the contribution of its originator, a former bomber, (later Pan Am) pilot and later still policeman named Gene Roddenberry. As producer, Roddenberry had been in charge of the original 1979 movie, made a decade after the original television series left the air. In the wake of its disastrous cost overruns Paramount had apparently reached an accommodation with him, whereby he was not to participate in the making of the second film but would receive a credit. The original film’s difficulties appear to have been concentrated in two areas: (1) a script that kept mutating (I was told that cast members received pages changes stamped not by the day but by the hour, as in, “Did you get the 4:30 changes?”) and (2) endless difficulties over the special effects. Nowadays, thanks to computer-generated imagery, much of what once consumed millions of dollars and thousands of man-hours seems like child’s play. But listening to Douglas Trumbull detail what went into creating Stanley Kubrick’s even earlier, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), one understands that all this eye candy had to be figured out literally frame by frame, utilizing endless trial and error by multiple FX houses as they experimented with spaceship models, how to photograph them convincingly, get rid of wires, create the illusion of activity inside them (would you believe tiny projectors, reflecting images off mirrors bounced inside?), etc. Special effects houses need huge sums of money for equipment to start up and later geeks to man them, change them, break them, and reconceive them.

But none of the foregoing altered the parameters of the universe Roddenberry had set up. He was emphatic that Starfleet was not a military organization but something akin to the Coast Guard. This struck me as manifestly absurd, for what were Kirk’s adventures but a species of gunboat diplomacy wherein the Federation (read America, read the Anglo-Saxons) was always right and aliens were—in Kipling’s queasy phrase—“lesser breeds”? Yes, there was lip service to minority participation, but it was clear who was driving the boat.

Ignorant, as I say, or arrogantly uninterested in precedent, I was intent on refashioning the second movie as a nautical homage.

“And the script?” Bennett prompted quietly.

“Well, here’s my other idea,” I told them, taking a deep breath and producing a yellow legal pad from under my chair. “Why don’t we make a list of everything we like in these five drafts? Could be a plot, a subplot, a sequence, a scene, a character, a line even . . .”

“Yes?”

“And then I will write a new script and cobble together all the things we choose.”

They stared at me blankly.

“What’s wrong with that?” I had been rather proud of this idea.

Now they glanced at one another before answering.

“The problem is that unless we turn over a shooting script of some sort to ILM [Industrial Light & Magic, George Lucas’s special effects house, contracted by Paramount to provide shots for the movie] in twelve days, they cannot guarantee delivery of the FX shots in time for the June release.”

I wasn’t sure I’d heard correctly.

“June release? What June release?”

That was when I was informed that the picture had already been booked into theaters—a factor that, in my ignorance, had never occurred to me.

I thought again. I must have been really stoked by this point, because the next thing that popped out was:

“Alright, I think I can do this in twelve days.” Why I thought this, I cannot now recall.

Again they looked at me, then at each other, and then down at my rug, as if something inscrutable was written there.

“What’s wrong with that?” I demanded.

Bennett sighed. “What’s wrong is that we couldn’t even make your deal in twelve days.”

I blinked. I was still relatively new to the business—this would be only the second film I’d directed)—and none of this made any sense to me.

“Look,” I countered impatiently, “Forget about my deal. Forget about the credit. Forget about the money. I’m just talking about the writing part, not the directing,” I inserted with emphasis. “All I know is that if we don’t do what I’m suggesting, make that list right here, right now—there isn’t going to be any movie. Do you want the movie or not?”

What would have happened had I not made this offer? Clearly the film would have been canceled for the nonce, the booking dates forfeited. Whether the studio would have plowed forward with yet another script for an opening in another season is a question no one can answer.

Everything changes with hindsight. Do I remember what happened next? I recollect their astonishment, but perhaps this is mythopoesis. I mean, who knew I would ever be trying to remember this stuff? What I do know is that we then made the list. It included Bennett’s original happy notion of using Khan (from the “Space Seed” episode, wherein Kirk rescues the genetically enhanced Khan and his followers, only to have Khan attempt to seize control of the Enterprise and, failing, marooned by Kirk along with a female member of the Enterprise’s crew who has fallen for him, on an asteroid or some such location); the Genesis Project (creating planetary life); Kirk meeting his son; Lieutenant Saavik (Spock’s beautiful Vulcan protégée); the death of Spock; and the simulator sequence (in which the Enterprise, under Saavik’s command, appears to be attacked in what later turns out to be what we would today call a war game. This sequence originally occurred—minus Spock’s participation—in the middle of one of the drafts). All these materials were culled higgledy-piggledy from the five different drafts that I never—to the best of my recollection—consulted again.

“Why can’t Kirk read a book?” I wondered, staring at the titles on my shelves. I pulled down A Tale of Two Cities, funnily enough the only novel of which it can be said that everyone knows the first and last lines.

Bennett and Sallin left and I went to work.

The View From the Bridge © 2009 Nicholas Meyer